glot_statusIntroduction to plotting

1 Good data visualisation

Alberto Cairo has identified four common features of good data visualisation (Spiegelhalter 2019:64–66):

Let’s see a few examples.

2 Information is (not) reliable

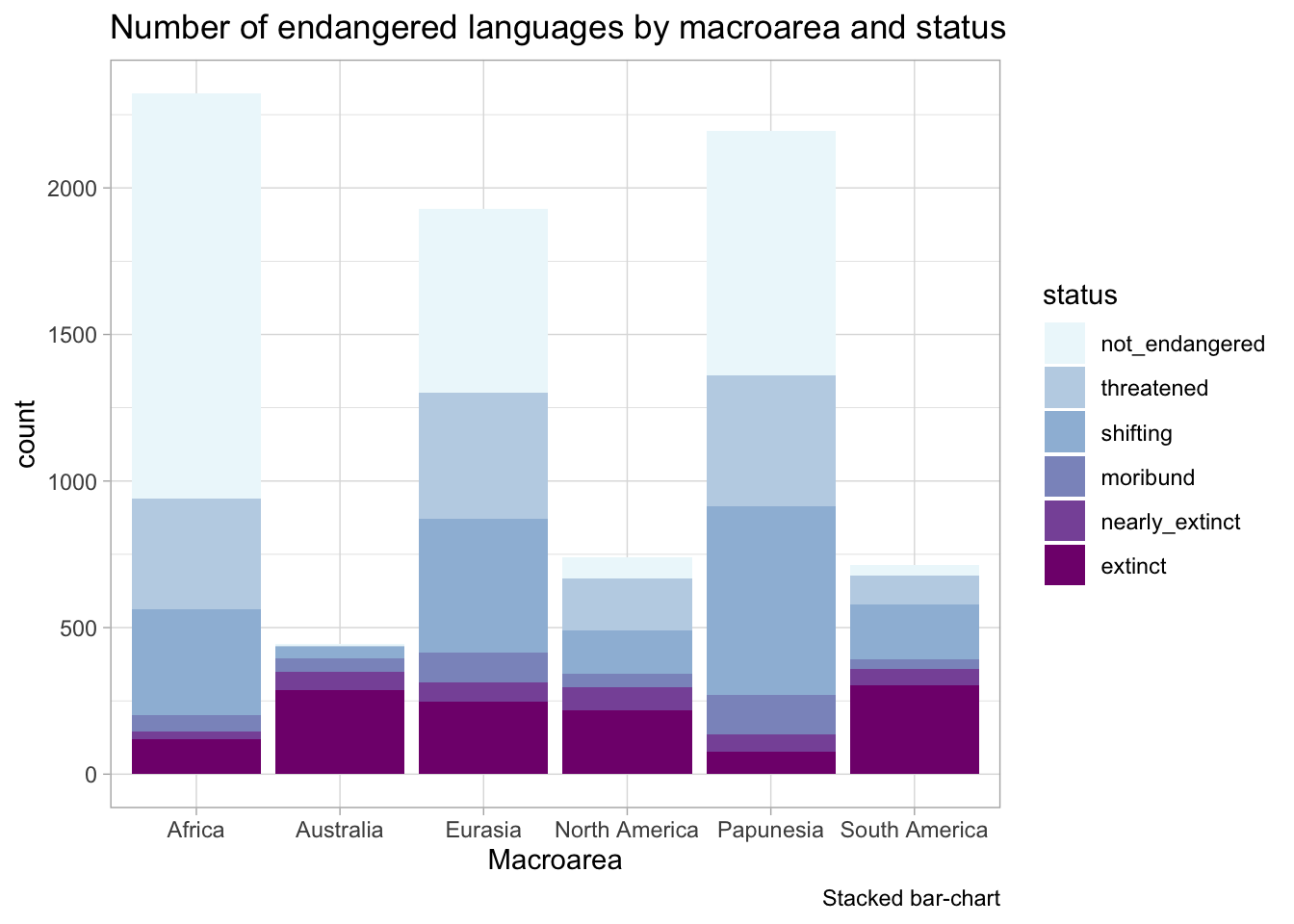

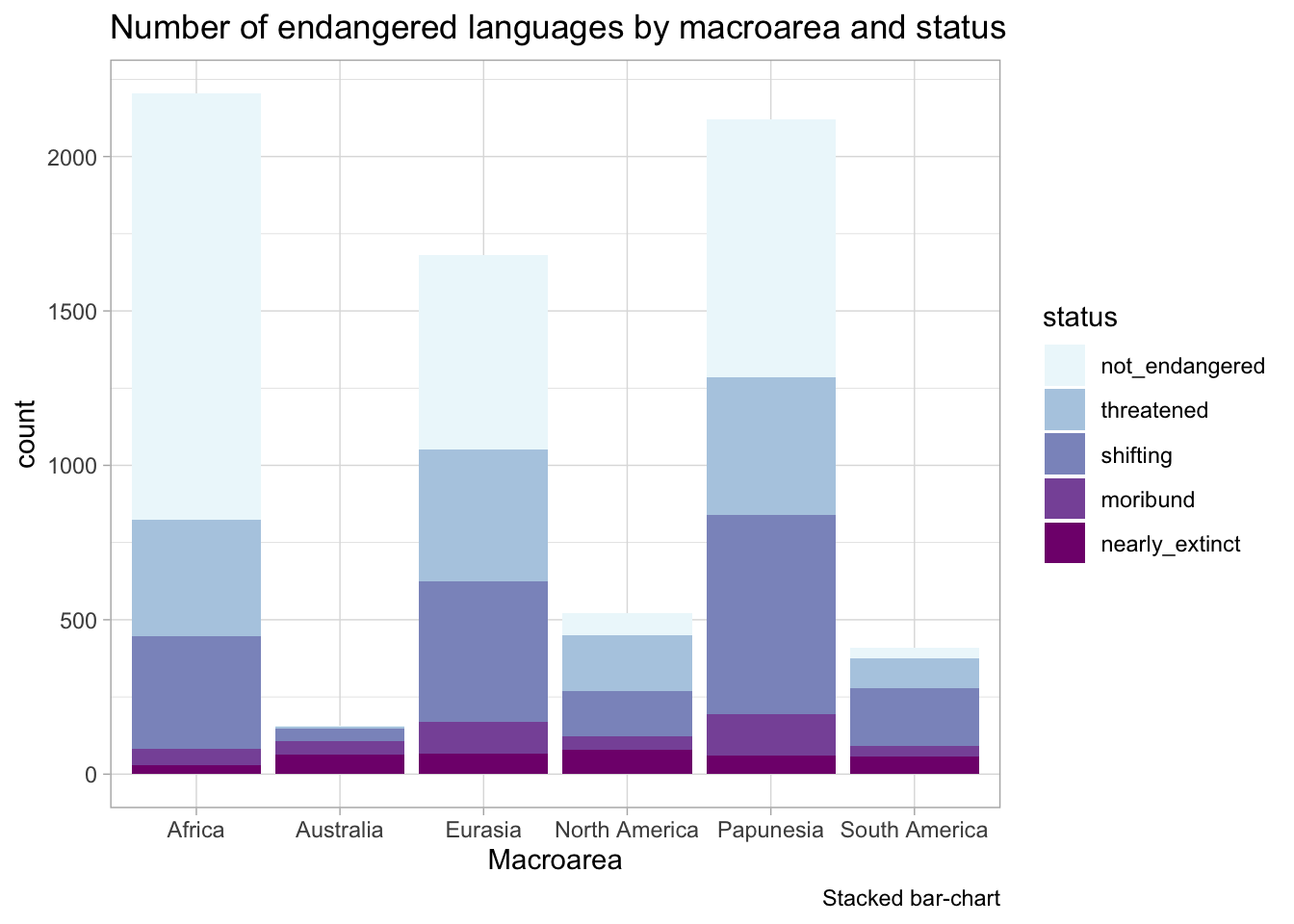

Let’s use the glot_status data. You will not see the code used to create the plots because you will learn about it in later tutorials, but if you are curious you can find the code here.

The following plot is titled Number of endangered languages by macroarea and status, but the plot contains both endangered and non-endangered languages.

We can fix that by filtering the data so that it contains only endangered languages.

3 Patterns are (not) noticeable

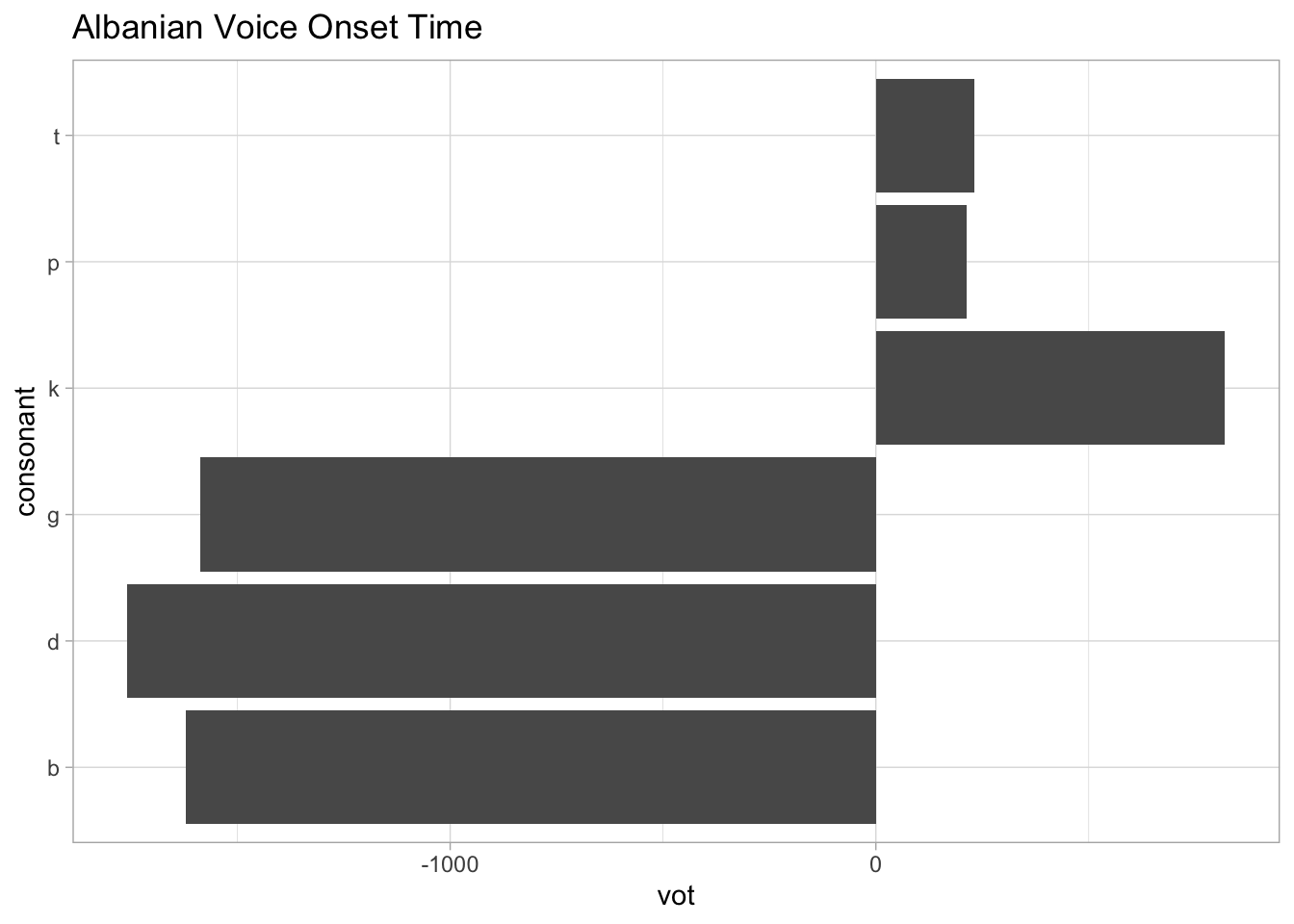

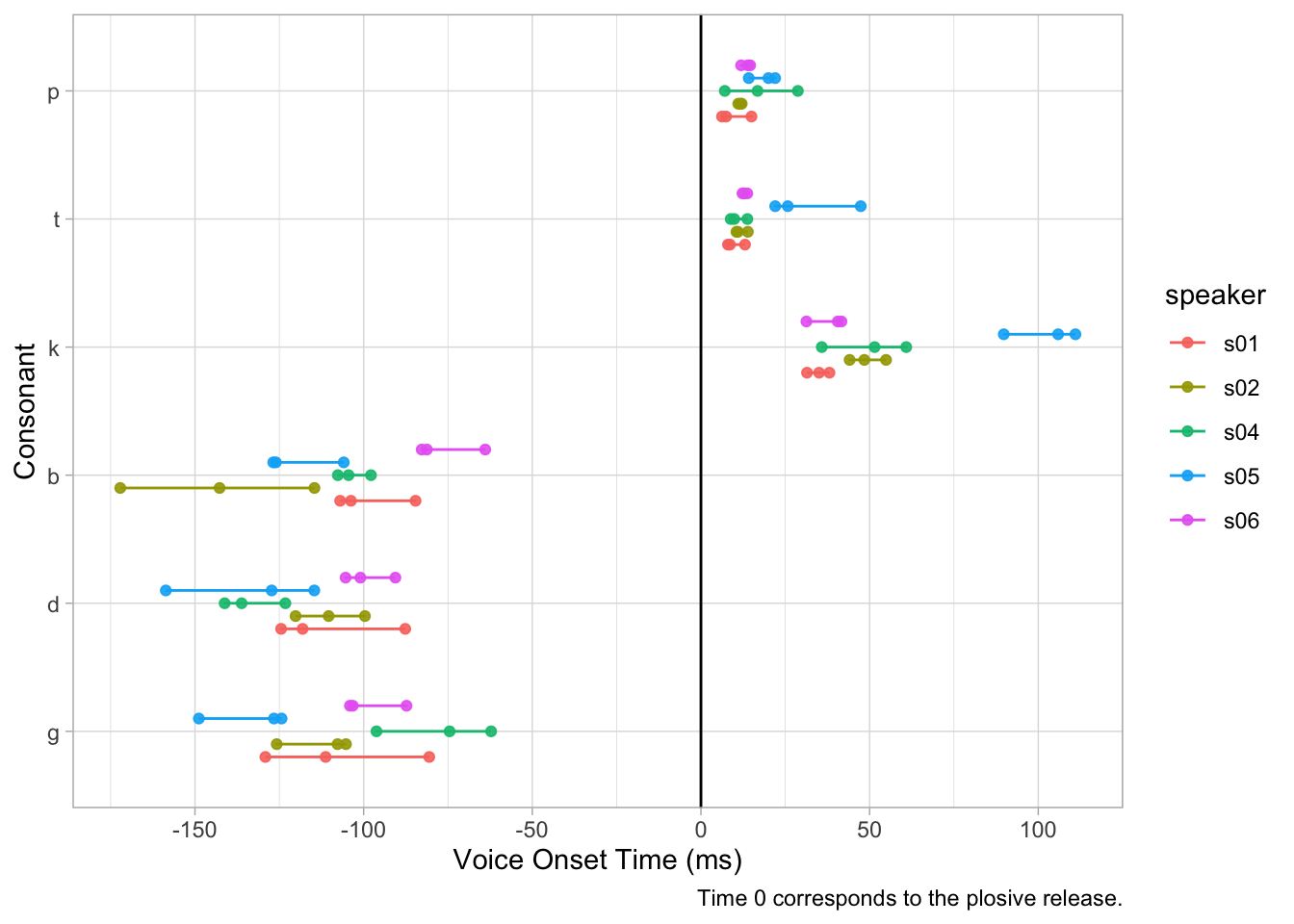

The albvot data contains data on VOT in Albanian. It has data from 6 speakers.

The following plot uses a bar chart to show the VOT of different stops, but what you can’t really see is that there is a lot of variability within and among stops and within and among speakers.

We can do better. The following plot shows individual measurements of VOT for different stops and speakers. Now an interesting pattern emerges: speaker 5 (s05) has particularly long VOT for /t/ and /k/ relative to the other speakers.

Bar charts are unfortunately overused in research, even in those cases when they are not appropriate. You can learn more about bar charts, and when to use them, in the Bar charts post.

4 Aesthetics (should not) get in the way

The graph above has a lot of issues:

- The bar length and thickness are not proportional. Compare Japanese with 123 million speakers vs English with 765 million speakers.

- The graph mixes two scales: million speakers and billion speakers. This makes it look as if Chinese does not have that many more speakers.

- The shade of orange of the bars does not seem to become proportionally darker with more speakers. Look at Arabic and Hindi: they have a very similar number of speakers but one bar is darker than the other.

- The three dudes speaking are just fillers. Are they really necessary? Also, they are all white men…

Can you find other issues?

See more examples on Ugly Charts.

5 (Does not) enable exploration

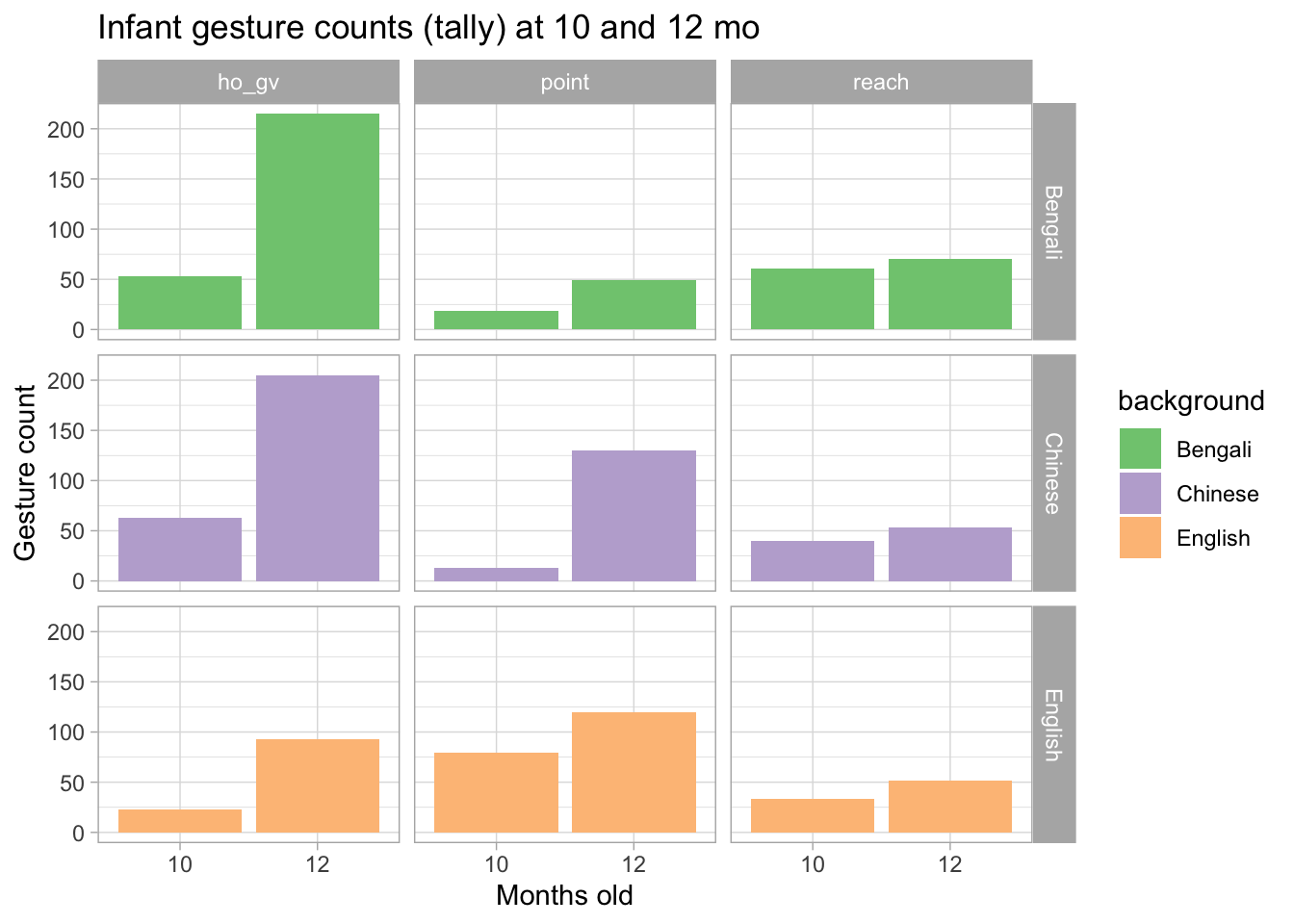

The plot below shows the number of gestures enacted by infants of English, Bengali and Chinese background as recorded during a controlled session. Three different types of gestures are shown: hold out and give gestures (ho_gv), index-finger pointing (point) and reach out gestures (reach). Moreover the plot shows the number of gestures at 10 and 12 months.

A bar chart is appropriate with count data, like in this case, but it does not allow for much exploration. Each infant was recorded at 10 and 12 months of age, but in the plot you don’t see whether individual infants changed their number of gestures. We can only notice that overall the number of gestures increases from 10 to 12 months old.

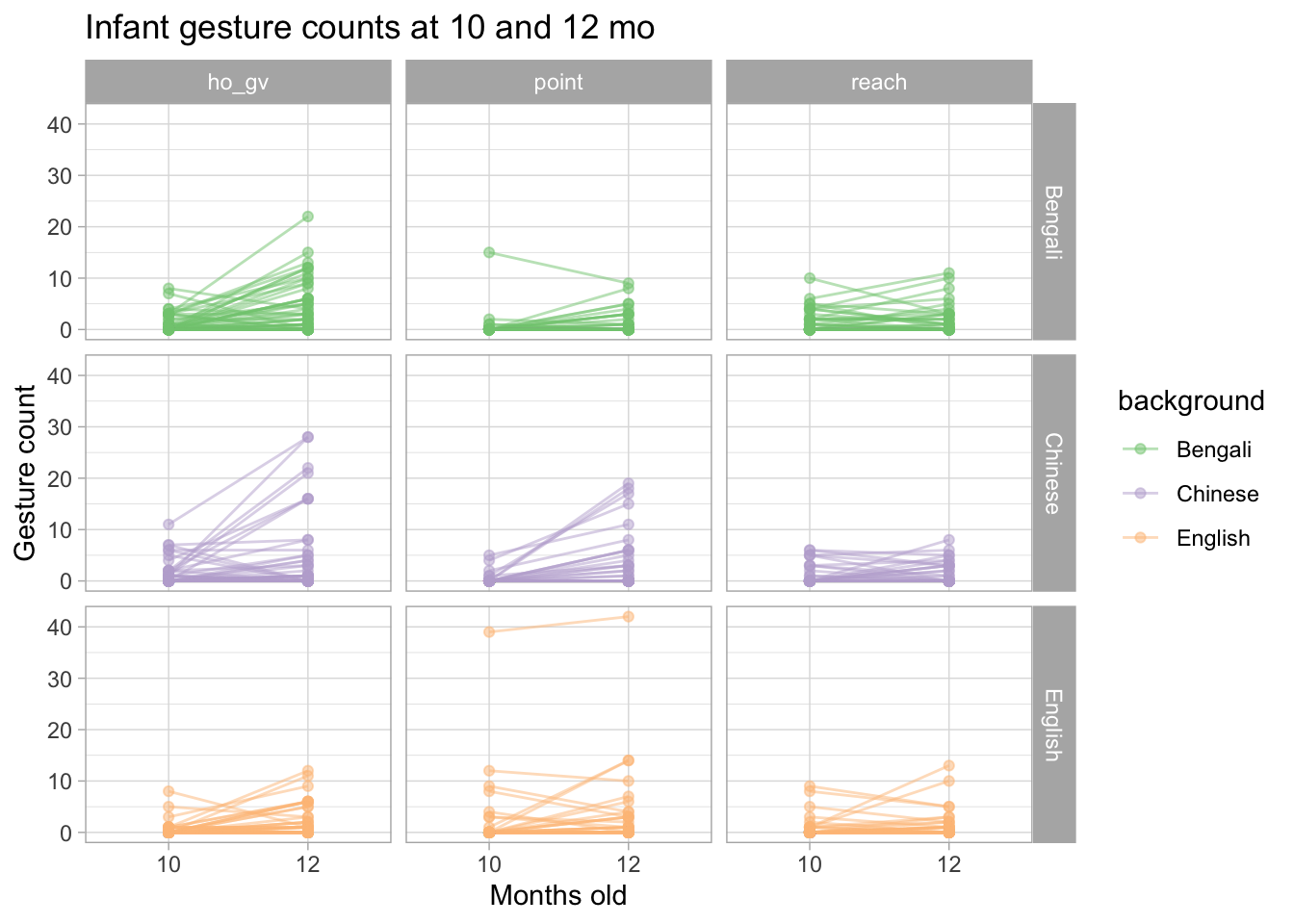

We can use a “connected point” plot: each infant is represented by a dot at 10 and 12 months and the dots of the same infant are connected by a line. This allows us to see whether an individual infant uses more gestures at 12 months.

You will notice that some infants don’t really use more gestures and others even use slightly less gestures. You would not be able to see any of this if you used a bar chart, like we used above.