What is statistics?

1 What is statistics?

Statistics is a tool. But what does it do? There are at least four ways of looking at statistics as a tool.

Statistics is the science concerned with developing and studying methods for collecting, analyzing, interpreting and presenting empirical data. (From UCI Department of Statistics)

Statistics is the technology of extracting information, illumination and understanding from data, often in the face of uncertainty. (From the British Academy)

Statistics is a mathematical and conceptual discipline that focuses on the relation between data and hypotheses. (From the Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

Statistics as the art of applying the science of scientific methods. (From ORI Results, Nature)

To quote a statistician:

2 What statistics is NOT

Statistics is a lot of things, but it is also not a lot of things.

Statistics is not maths, but it is informed by maths.

Statistics is not about hard truths not how to seek the truth (see Inference and uncertainty).

Statistics is not a purely objective endeavour. In fact there are a lot of subjective aspects to statistics (see below).

Statistics is not a substitute of common sense and expert knowledge.

Statistics is not just about \(p\)-values and significance testing.

As Gollum would put it, all that glisters is not gold.

3 Many Analysts, One Data Set: subjectivity exposed

In Silberzahn et al 2018, a group of researchers asked 29 independent analysis teams to answer the following question based on provided data: Is there a link between player skin tone and number of red cards in soccer?

Crucially,

69% of the teams reported an effect of player skin tone, and 31% did not.

In total, the 29 teams came up with 21 unique types of statistical analysis.

These results clearly show how subjective statistics is and how even a straightforward question can lead to a multitude of answers.

To put it in Silberzah et al’s words:

The observed results from analyzing a complex data set can be highly contingent on justifiable, but subjective, analytic decisions.

This is why you should always be somewhat sceptical of the results of any single study: you never know what results might have been found if another research team did the study. This is a reason for why replicating research is very important.

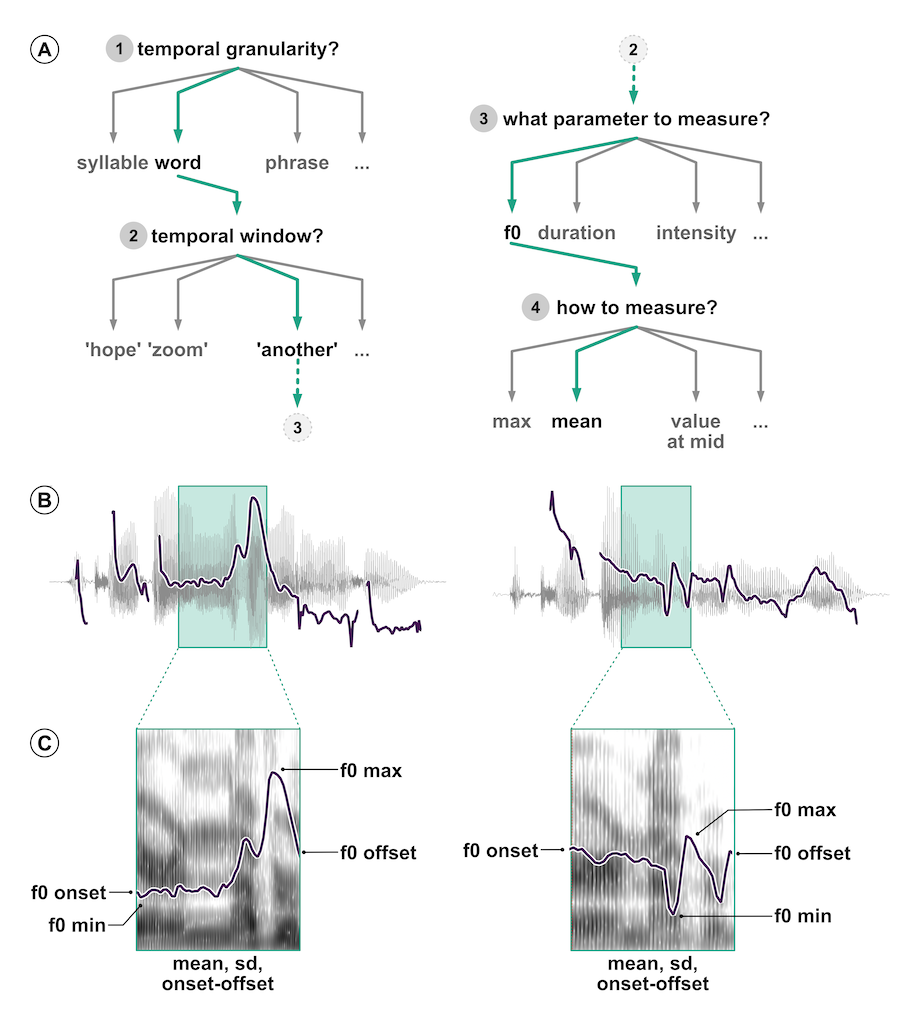

Coretta et al 2023 tried something similar, but in the context of the speech sciences: they asked 30 independent analysis teams (84 signed up, 46 submitted an analysis, 30 submitted usable analyses) to answer the question Do speakers acoustically modify utterances to signal atypical word combinations?

Incredibly, the 30 teams submitted:

- 109 individual analyses. A bit more than 3 analyses per team!

- 52 unique measurement specifications and 47 unique model specifications.

Nine teams out of the thirty (30%) reported to have found at least one statistically reliable effect (based on the inferential criteria they specified). Of the 170 critical model coefficients, 37 were claimed to show a statistically reliable effect (21.8%).

—Coretta et al, 2023

4 The “New Statistics”

The Silberzahn et al and Coretta et al studies are just the tip of the iceberg. We are currently facing a “research crisis”.

Cumming 2014 proposes a new approach to statistics, which he calls the “New Statistics”, in response to the research crisis.

The New Statistics mainly addresses three problems:

Published research is a biased selection of all (existing and possible) research.

Data analysis and reporting are often selective and biased.

In many research fields, studies are rarely replicated, so false conclusions persist.

To help solve those problems, it proposes these solutions (among others):

Promoting research integrity.

Shifting away from statistical significance to estimation.

Building a cumulative quantitative discipline.

5 The Bayesian New Statistics

Kurschke and Liddell 2018 revisit the New Statistics and make a further proposal: to adopt the historically older but only recently popularised approach of Bayesian statistics. They call this the Bayesian New Statistics.

The classical approach to statistics is the frequentist method, based on work by Fisher, and Neyman and Pearson. Frequentist statistics is based on rejecting the “null hypothesis” (i.e. the hypothesis that there is no difference between groups) using p-values.

Bayesian statistics provides researchers with more appropriate and more robust ways to answer research questions, by reallocation of belief/credibility across possibilities.

You can learn more about the frequentist and the Bayesian approach here.